Reflow Amsterdam – redesigning urban textile flows

Meet the Amsterdam Pilot

The Amsterdam REFLOW Pilot

The REFLOW Pilot cities are progressing activities which aim to explore, analyse and embed circular practices in key local industries. In Amsterdam, their focus is textiles. This overview presents the latest from the Pilot, which sees collaboration between citizens, academia, industry and the maker community.

Visiting Amsterdam’s textile sites

Together with Master Industrial Design students from the KABK, the Amsterdam REFLOW team visited two locations of a key organisation in the city’s circular textile chain.

At the Amsterdam waste collection point in Westelijk Havengebied, lorries with scrap iron, appliances and other reusable materials come and go. The area with textile waste delivers an overwhelming sight. When the corona crisis erupted and the export of textiles abroad came to a halt, textiles were piling up rapidly. At that moment, the material had nowhere to go. An immense hall, filled with 2.4 million kilos of textiles, is ready for a new life in second-hand clothing stores in Europe and Africa, or to be processed and repurposed for other applications and products in various industries.

“2.4 million kilos is about a monthly amount of textile waste, collected and recycled nationally.”

The 2.4 million kilos are collected monthly and processed nationally by Sympany, says Jan-Maarten Zeldenrust, advisor fashion, collection- and reuse at Sympany, which is a company that focuses on the collection and sorting of textile waste. The REFLOW team is visiting two of Sympany’s locations to gain insight into the textile flows in and around the city. REFLOW’s Amsterdam pilot examines the textile flow and aims to work towards circular textiles. Therefore, this site visit provided many insights and leads to the continuation of our research.

The clothes that end up at the waste collection point in Amsterdam, are collected in textile bins throughout the Netherlands. The clothes are collected, packed (see image 1) and then sorted before being sold or repurposed. In general, sixty per cent of the clothing can still be worn – the rest gets reprocessed and is used to make cleaning cloths or acoustic damping materials. “In the Netherlands, people relatively consume a lot of “fast fashion”, consisting of rapidly changing collections that respond to short trends and are also quickly “out of fashion” again”, says Zeldenrust. Not surprisingly, the amount of clothing that gets discarded in the Netherlands is very high.

What are the challenges of discarding textiles correctly?

Viewing the textile recycling process from the inside helps to get a better understanding of the challenges of circular textile and the work that needs to be done by the REFLOW pilot in Amsterdam. The vast majority of our textiles aren’t discarded properly and therefore do not get recycled as well as they could. In the Amsterdam pilot for Reflow, Waag, BMA Techne, Pakhuis de Zwijger and the Municipality of Amsterdam are working together on a circular textile flow for Amsterdam. This is an objective that fits the circular ambitions of Amsterdam: in 2030, the city must use 50 per cent less new resources. By 2050, the city should be fully circular.

Back at the Sympany centre in Utrecht, it becomes clear that the textile bins are not only used for clothing. The Sympany employees, who do the first check of the badges, come across the craziest things lying between the collected clothing and textiles. Food waste, diapers, electronic appliances and even weapons, living pets, pieces of jewellery and gold were found. ‘People use the textile bins for all their waste,’ a sorting employee explains. This is a big problem, since food waste, wet textiles and, for example, diapers can make a whole batch of worn textiles useless.

‘ Food waste, diapers, electronic appliances and even weapons, living pets, jewellery and gold were found. People use those bins for all their waste. ’

Macro fashion politics

The clothing collected by Sympany gets rated based on its quality. The ‘best’ clothing often ends up in Dutch second-hand clothing stores. Lower-quality material is purchased by mostly Eastern European and African customers. However, the recycling of clothing is not just about the supply, Zeldenrust explains. Customers who buy second-hand clothing from Africa often have specific wishes. ‘Not all trends we have here are well received by buyers of second-hand clothing. We received comments about the number of jeans with holes in them. Customers asked if we sent the wrong shipment, or if there was something wrong with the sorting system. This kind of jeans was totally trendy here, but the buyers had serious doubts about them. The type of clothing that is collected varies between European countries.’

REFLOW Amsterdam

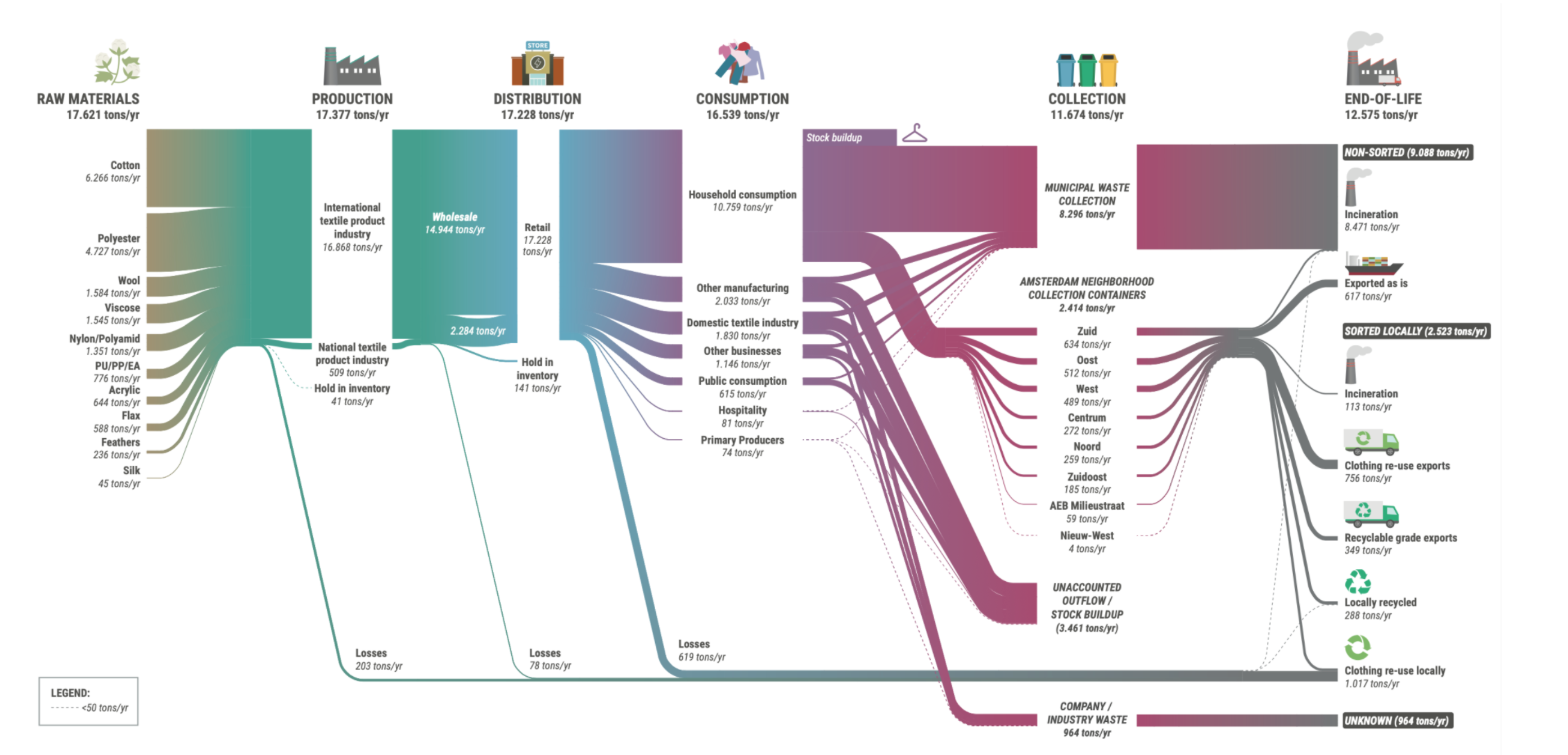

The Amsterdam REFLOW team started their work with a Material Flow Analysis, (see image 2) made by project partner Metabolic, that shows the current textile streams. This was the starting point for the design of a circular textile flow.

Our objectives

In order to move from a linear to a circular textile flow, the Amsterdam Pilot designed a strategy that contains different focus points while working on an overarching roadmap for the upcoming years:

- Since a lot of textiles are trashed in the normal bin, the clothing and textiles go straight to incineration. The amount of correctly collected textiles needs to be increased (without people buying and trashing more) to provide feedstock for the recycling industry too, ultimately, supply all of us with products that contain recycled fibres.

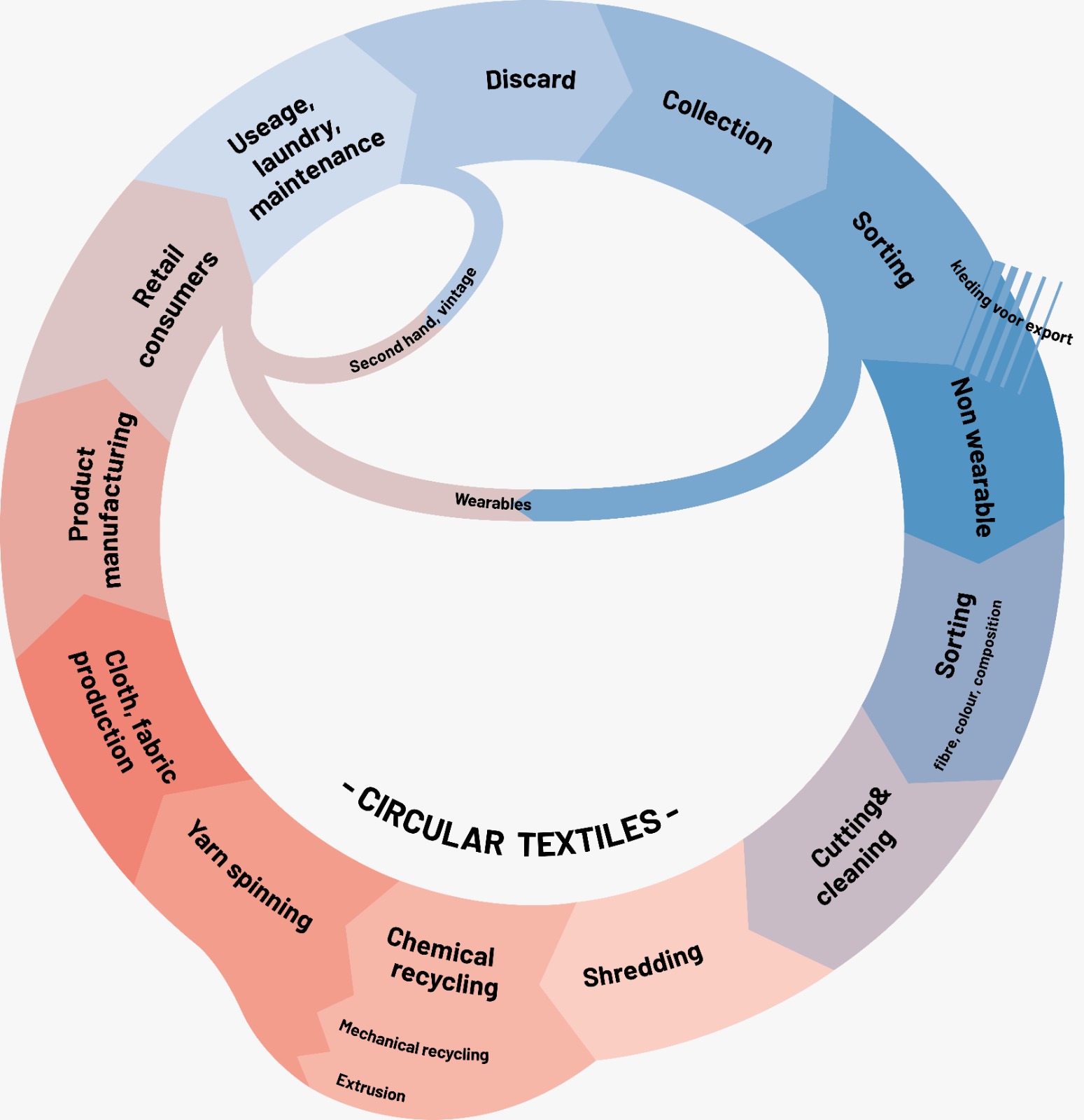

- Use the increase of correctly discarded and collected textile to further design and operationalise the wheel involving different stakeholders of each step of the ‘Textile Wheel’ (see image 3), bringing supply and demand together.

- Discarding less and extending the life cycle of textiles by repairing, reusing and revaluing through a series of workshops and collaboration with educational institutes.

- Exploring design for circularity and circular textiles through a series of workshops and public activities.

Our textiles booklet is to be released soon

To be able to explain the steps of the Amsterdam Circular Textile Wheel, an explanatory booklet is developed by BMA Techne. Textile circularity in 16 steps! Every chapter in the book refers to one step in this wheel and gives you concrete building blocks and tips and tricks on how to handle the steps. By the end, this provides a full vision on circular textiles in the city.

The first chapter is due by the end of November and every other week, another chapter will be published. Check out the social channels and the REFLOW website for the upcoming events!

Want to get in contact with the local pilot team? Email us at amsterdam@reflowproject.eu